Tag: The Secret History Of One Of The Most Sampled Albums Of All Time

The Secret History Of One Of The Most Sampled Albums Of All Time

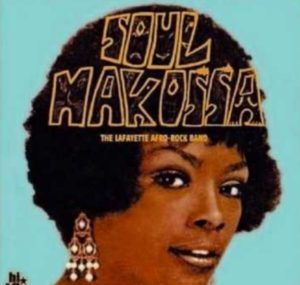

In July, members of Vinyl Me, Please Classics will receive the first official U.S. release — with the original artwork — of Lafayette Afro-Rock Band’s Soul Makossa, the debut LP from a cracking U.S. funk band that recorded in France and which provided the backbone for much of early rap music. You can can sign up here.

In 1971, the Bobby Boyd Congress fled Long Island due to funk saturation and fear of death. Both were ineluctable realities that could torment any band aspiring to breakthrough in a New York City convulsing with kinetic break beats, opiate addiction, and the casket lottery of the Vietnam draft. So in the tradition of Josephine Baker and James Baldwin, the band decamped for the city of lights.

No one would mistake the Paris of 1971 for a funk mecca. The suave chansons of Jacques Brel and Serge Gainsbourg’s Lolita-lite baroque pop ruled the airwaves as a Gaullist government attempted to erase the lingering specter of 1968’s near-revolution. The change offered the Roosevelt natives the potential for adventure and opportunities ostensibly occluded in a five boroughs world controlled by funk linchpins, Mandrill, the Fatback Band and B.T. Express.

Things didn’t go as planned. Despite his prodigious gifts as a singer, songwriter, saxophone player and bandleader, Bobby Boyd failed to even become the most famous musician named Bobby Boyd (a Texan country songwriter outranks him). His eponymous 1971 debut later became a holy grail of rare groove fetching up to 1500 Euro’s a copy, but the limited edition run of 300 vanished into the Gauloises-wreathed attics of the left bank. Swiftly reconsidering his decision to expatriate, Boyd returned to American anonymity, leaving his band to parse the New Wave wanderings of a post-Weekend world.

The Americans in Paris established their habitué inside the clubs of the Barbes district, a swath of the 18th arrondissement largely populated by North African immigrants. Amidst the avenues of vegetable stalls and halal butchers, kebab stands and African hair salons, the New Yorkers conjured a vulcanized funk, durable and lubricious, adopting the ras el hanout of the neighborhood to their loose-limbed American swing. Discovery was imminent and arrived via a peripatetic Parisian harmonica player who had once attempted to teach French to a pre-adolescent Stevie Wonder under the orders of Berry Gordy.

His name was Pierre Jaubert, a raconteur whose storied resume almost reads like a one-man “Losing My Edge.” The stories bequeathed seem almost too surreal to be true. He was in Detroit in 1962, teaching Lil Stevie how to sing in French and turning down Gordy’s offer to run Motown’s international operations (Pierre hated the idea of being in an office). He met Smokey Robinson and watched the sorcery of Motown’s in-house Merlin, Norman Whitfield, brewing masterpieces inside that converted house studio, Hitsville USA, with low-hanging ceilings and a grand piano. He rubbed shoulders with Marvin Gaye and flirted with a teenaged Diana Ross, before “settling” for Mary Wells.

He was in Chicago to witness the birth of Windy City soul, catching the nascent sessions of Curtis Mayfield and Phil Upchurch and the Dells. If you listen close on some of those Kennedy-era spells, he once claimed you could hear him breathing. Then sometime shortly before the Age of Aquarius took hold, he returned to Paris because in America, everything seemed to be at “right angles.”

The story somehow only gets more random. In Paris, Jaubert doubles down on his jazz roots, laying down tracks with Charlie Mingus and Archie Shepp. He doesn’t merely dabble in the blues, he commences sessions with John Lee Hooker and Memphis Slim. On a return sojourn to America, a chance encounter with a Bay Area packing clerk named John Fogerty leads to the discovery of Creedence Clearwater Revival.

“The subsequent alchemy would yield a grease fire funk classic that became one of the most sampled albums in hip-hop history.”

“He told me, oh I have a group,” Jaubert recalled in 2011. “I heard his tape. It was very good. So when I spoke to Saul [Zaentz, the owner], I said, ‘Hey, the guy who is working for you, you should record him.’ So that is how Creedence Clearwater Revival ended up on Fantasy records.”

As a reward for ushering “Proud Mary” into the world, Jaubert successfully finessed the rights for a friend to release CCR’s music in France. That victory led to Jaubert being given free rein to indulge any sonic whim. This is when the Lafayette Afro-Rock Band finally glides into the mise en scene.

In the wake of their front man’s flight, the one-time Congress rebranded themselves as “Ice,” an alias they were still using when Jaubert received a phone call from a friend. Said friend had a studio and recognized Ice’s talent, but didn’t know what to do with an American soul-funk crew. So he called up his friend Jaubert, the house producer at Parisound Studios. In Jaubert’s 2011 recollection, the call went a little something like this: “Look, I have these guys from New York. Please take these guys. I don’t want to see them again. They want money for their music, please take care of that. Bye Bye.”

Money was a practical consideration almost entirely absent from the subsequent proceedings. Their initial foray with Jaubert, Each Man Makes His Own Destiny, flopped miserably. The music was fine, but it was commercial kryptonite. If not for a chance conversation with the Cameroonian afro-funk legend, Mani Dibango, it’s possible that it would’ve been the last anyone ever heard of the transplanted New Yorkers. But Dibango insisted that Jaubert should continue working with them and try to score them a hit. First, there was the matter of their name.

“I could not call it Ice, because first legally you cannot register the name Ice. There are many names like this that you cannot record under or register commercially. That is why you have so many variations. Ice Cube, Ice T, everybody is using Ice,” Jaubert said in 2011. “I thought, I’ll make a name that is easy to register to record under. In France we use complicated names, so the Lafayette Afro-Rock band, that name was kind of complicated. So I invented that and registered the name immediately. It was a group that did not exist. There was no such group as [The] Lafayette Afro-Rock Band. I had to invent them.”

Inspired by what he’d learned from Gordy, Jaubert conceived the Lafayette players as a rotating ensemble that could double as the Parisound house band — the Gallic equivalent of Motown’s Funk Brothers. Jaubert owned the name and swapped in a fungible cast of guest players, but the core trinity was comprised of Frank Abel, the keyboard player and pianist; Michael McEwan, the electric guitar player; and Arthur Young, who handled drums and percussion. The subsequent alchemy would yield a grease fire funk classic that became one of the most sampled albums in hip-hop history.