Tag: monarch butterfly

California’s most famous butterfly nearing death spiral

An alarming, precipitous drop in the western monarch butterfly population in California this winter could spell doom for the species, a scenario that biologists say could also plunge bug-eating birds and other species into similar death spirals.

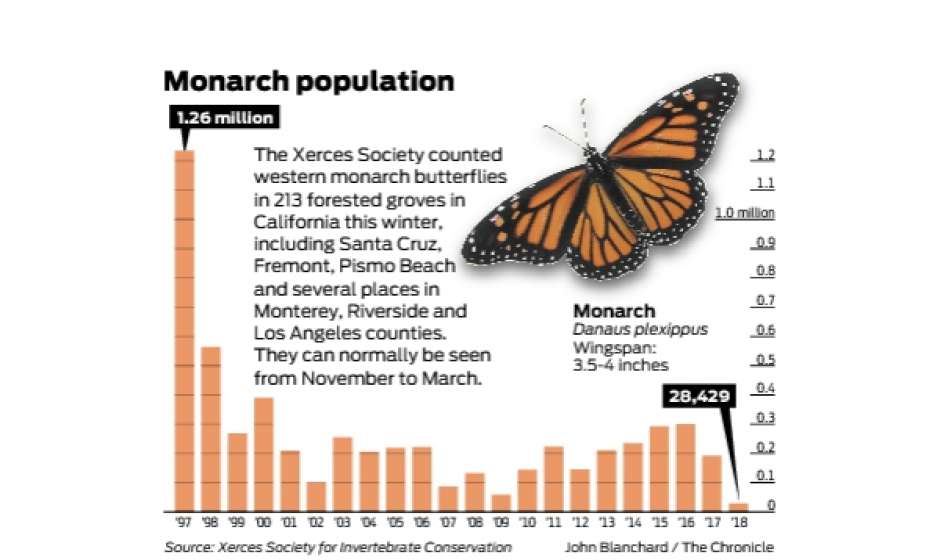

Only 28,429 of the striking orange-and-black butterflies were counted at 213 sites in California, an 86 percent drop from a year ago, according to the final tally of the annual Thanksgiving and New Year’s counts released Thursday by the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

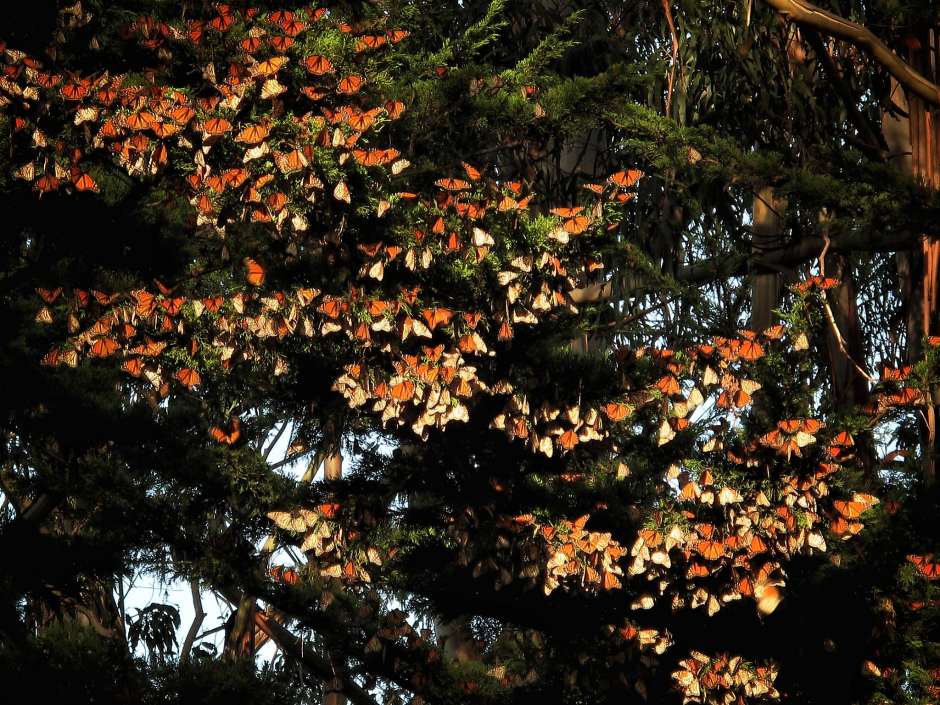

That’s a 99.4 percent decline since the 1980s, an all-time low for the Pacific Coast, where an estimated 10 million monarchs once blanketed trees from Marin County to the Baja California peninsula, providing, by all accounts, a spectacular winter display of color.

Scientists knew things were bad for the western monarch, but then “there was this other order of magnitude drop,” said Emma Pelton, a conservation biologist for the Xerces Society, an international nonprofit whose mission is to protect invertebrates and their habitats. “It’s mind-boggling. We’re now down below 1 percent of the historic population.”

The death of monarchs does not bode well for other insects, like bees, or bird species that make their living eating insects.

Monarchs in trouble

Western monarch butterflies spend the winter in more than 300 forested groves along the California coast, including large populations in Riverside and Los Angeles counties, Pacific Grove, Monterey and at Natural Bridges State Beach in Santa Cruz. They can normally be seen from November to March.

With the number of butterflies declining rapidly, here are four things governments and the public can do to help:

Protect and manage California overwintering sites.

Restore breeding and migratory habitat in California, particularly habitat along the coast range, foothills and Sacramento Valley.

Stop spraying pesticides and herbicides near milkweed, their primary habitat.

Protect, manage, and restore summer breeding and fall migration habitat outside of California.

“It is very apt to say this is a canary in a coal mine for a lot of our native pollinators,” Pelton said. “There’s a tight link in a loss of insects and our songbirds, which rely on insects. We have declines in songbirds, and I think that links directly to declines in insects.”

The die-off has been blamed on a variety of things, including urban sprawl, the spraying of pesticides and herbicides on corn and soybean crops, and the plowing under of the monarch’s milkweed habitat along their migratory route.

A University of Michigan experiment published in July found that higher carbon dioxide levels have reduced a natural toxin in milkweed that feeding monarch caterpillars utilize to fight off parasites. The study showed a 77 percent reduction in parasite tolerance in the butterflies hatched on milkweed grown under high concentrations of carbon dioxide, which comes from car and factory emissions and is what scientists say is the primary cause of climate change.

If nothing is done, Pelton said, the California butterflies, first observed by a Russian expedition looking for a passage across the Arctic Ocean in 1816, could be on an “extinction vortex,” a time when there are not enough butterflies left to recover.

Nobody knows how low the monarch population can go before it’s too late, but a 2017 study funded by The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and published in the journal Biological Conservation calculated that the point of no return would likely come when there are fewer than 30,000 butterflies.

The more abundant eastern monarchs, which spend their winters in Mexico instead of California, are famous because they cover whole sections of forest in a kaleidoscope of color. It is the largest insect migration in the world, but it too is in trouble. The eastern monarchs have declined more than 90 percent since 1996, when scientists estimated there were 1 billion nesting in the trees.

The journeys of both populations are remarkable in that it takes several generations of butterflies to make the six- to nine-month-long trek south for the winter. When they head back, starting in February or March, the mothers will die after laying eggs on milkweed, where the caterpillars grow up. Once they are ready to fly, the young butterflies somehow know where to go, without ever having even seen their mothers.

The California population is declining at an average of 7 percent a year, according to the 2017 Fish and Wildlife study. At the time, there were about 300,000 monarchs in California. That’s slightly worse than the 6 percent drop seen in the eastern monarch population.

“If this prediction is true, we are now below the quasi-extinction threshold,” Pelton said. “This is a crisis.”

There are two major migrations of monarch butterflies — the eastern and western populations — which scientists believe divide themselves at the Rocky Mountains when they head south for the winter from their summer homes in Canada and the Pacific Northwest.

In all, monarch populations in North America have plunged more than 95 percent since the 1980s, researchers have said.

Article via SFChronicle