Florida Man Dumps Port-A-Potty Waste In 7-Eleven As Revenge, Police Say

As criminal accusations go, this one is pretty crappy.

A Florida man is accused of dumping a bucket containing human feces and urine inside a St. Petersburg 7-Eleven.

Damian A. Simms’ alleged act of criminal caca happened early Wednesday, according to The Smoking Gun. He “apparently obtained the waste from a portable toilet,” the site reported.

Splattered poop got on a straw hat and a do-rag, with a total estimated value of $28.

The 41-year-old Simms was ID’d by the store manager and recorded on surveillance video, according to the police report.

It’s possible the alleged bowel movement bucket dump was an act of revenge: The police report notes that Simms was banned from the store in May.

Simms was charged with trespass and criminal mischief, both misdemeanors. As of Friday, he was still in the Pinellas County Jail in lieu of $300 bond.

He has been ordered to stay away from the 7-Eleven and its manager, according to Fox News.

READ MORE FROM HUFFPOST

DJ Jazzy Jeff Peter piper routine

Nice! This is REAL HIP HOP

The Happytime murders movie trailer

This keep showing up in my YouTube recommended for you I guess it was meant to be posted. Release dates on my birthday that’s a good thing ! LOL

“We Rise Together, Homie”

Today I got time Cuz! If only the NFL players would do this. If only black folks who were being racially nagged and chastised would do this. This is what power of the people looks like.

An interview with Antoine Dangerfield, whose video of an Indianapolis wildcat strike went viral this week — and led to his firing. He doesn’t regret it, though.

US labor history is full of moments of tremendous drama and upheaval. That history is riveting stuff, but getting a raw, unfiltered view of the human drama of workers fighting their bosses on the shop floor, the place where the day-to-day confrontation between workers and bosses takes place (and occasionally boils over), is rare.

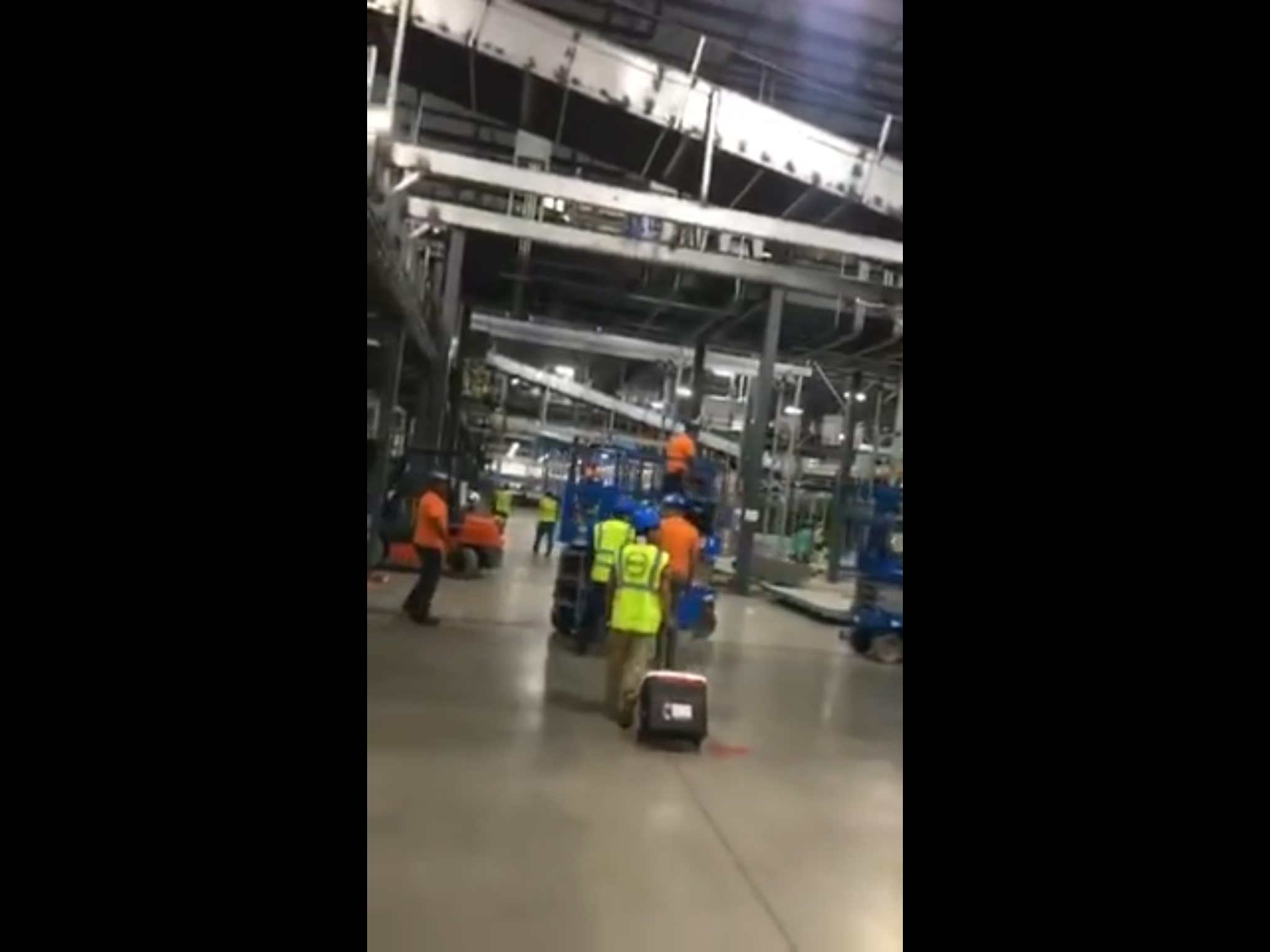

Which is what makes Antoine Dangerfield’s recent viral video a must-watch. A thirty-year-old welder in Indianapolis, Dangerfield worked for a construction contractor building a UPS hub. On Tuesday, he says that a small number of Latino workers (millwrights, welders, and conveyor installers, in his telling) working for a different contractor but in the same hub were ordered home after disobeying the orders of a white boss he calls racist.

In response, the entire group of workers — over a hundred, in Dangerfield’s estimation — walked out.

Dangerfield caught their wildcat strike on camera at the moment they walked off the job. In his video, he is positively giddy watching them shut down their massive workplace.

“They are not bullshitting!” he says as Latino workers walk off. Referring to the boss, he says, “They thought they was gonna play with these amigos, and they said, ‘aw yeah, we rise together, homie.’ And they leaving! And they not bullshitting!”

After all the workers are gone, Dangerfield gives the viewer a tour of the empty hub. He’s incredulous: “Ain’t no grinding, cutting, welding — this motherfucker dead-ass quiet. The Mexicans shut this motherfucker down.”

Since he posted the video on Wednesday, the footage has been viewed millions of times on Facebook (two million) and YouTube (nearly eight hundred thousand) and on sites like WorldStarHipHop (three hundred thousand). It also, as he explains in this interview, led to his firing. Dangerfield thinks it’s worth it, though.

Jacobin managing editor Micah Uetricht spoke with Dangerfield on Thursday afternoon. Neither could track down the striking workers in the video, but Dangerfield spoke about what was a “life-changing” experience for him. The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Our

US labor history is full of moments of tremendous drama and upheaval. That history is riveting stuff, but getting a raw, unfiltered view of the human drama of workers fighting their bosses on the shop floor, the place where the day-to-day confrontation between workers and bosses takes place (and occasionally boils over), is rare.

Which is what makes Antoine Dangerfield’s recent viral video a must-watch. A thirty-year-old welder in Indianapolis, Dangerfield worked for a construction contractor building a UPS hub. On Tuesday, he says that a small number of Latino workers (millwrights, welders, and conveyor installers, in his telling) working for a different contractor but in the same hub were ordered home after disobeying the orders of a white boss he calls racist.

In response, the entire group of workers — over a hundred, in Dangerfield’s estimation — walked out.

Dangerfield caught their wildcat strike on camera at the moment they walked off the job. In his video, he is positively giddy watching them shut down their massive workplace.

“They are not bullshitting!” he says as Latino workers walk off. Referring to the boss, he says, “They thought they was gonna play with these amigos, and they said, ‘aw yeah, we rise together, homie.’ And they leaving! And they not bullshitting!”

After all the workers are gone, Dangerfield gives the viewer a tour of the empty hub. He’s incredulous: “Ain’t no grinding, cutting, welding — this motherfucker dead-ass quiet. The Mexicans shut this motherfucker down.”

Since he posted the video on Wednesday, the footage has been viewed millions of times on Facebook (two million) and YouTube (nearly eight hundred thousand) and on sites like WorldStarHipHop (three hundred thousand). It also, as he explains in this interview, led to his firing. Dangerfield thinks it’s worth it, though.

Jacobin managing editor Micah Uetricht spoke with Dangerfield on Thursday afternoon. Neither could track down the striking workers in the video, but Dangerfield spoke about what was a “life-changing” experience for him. The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

MU

Where do you work?

AD

It’s a contractor that’s doing a UPS superhub. They fired me about [the video], though.

MU

Really?

AD

They’re real mad about it. They tried to pay me $250 to take it down. But there’s nothing I could do about it. I didn’t expect it to be this big.

MU

So what happened?

AD

There was a safety guy. He was just a racist, basically — always messing with anybody who’s not white. The Hispanics just stayed out of his way. They warned each other when he came because they knew he was always messing with them, taking pictures and videos, trying to get them fired.

We have safety meetings, and we usually have a translator [for Spanish speakers] because there are so many. On Tuesday, we had a safety meeting, and like I said, the Mexicans don’t really like [the safety coordinator].

He asked one of the Mexicans to come up and translate. He didn’t wanna do it. [The coordinator] got mad, real red-faced. Next thing you know, he dismissed the meeting. So he’s walking around just sending them home, trying to fire them. So he sent like five or six of them home.

So the Hispanics got together and were like, “Nah. We got families and kids. We’re not about to let these dudes just do whatever.” So they took a stand.

MU

Do they have a union?

AD

Nah. They just decided today’s the day. They fired the [safety coordinator], though. And they fired me, too, for the video. But there wasn’t one [worker] left in the building.

MU

How long had there been issues with the safety guy?

AD

As soon as he started. It’s been three or four months. I’ve been there since January.

MU

So what happened when the video went up?

AD

The owners of [the construction contractors] came down, corporate people from UPS.

MU

From UPS?!

AD

That’s what people were telling me. Because I went back to pick up my last check and my welding gear. That was when they offered me $250 to take it down. It was at 1.1 million views on Facebook at that point. So there was nothing I could do.

I was shocked. I come in here every day. The last video I posted got two likes! I wasn’t trying to harm anybody.

MU

How did you feel watching them walk off the job?

AD

I just felt that power, man. It just felt good. They were walking out with their heads up, strong. It touched me. That’s why I was like, wow, this is beautiful. It was beautiful that they came together like that — stood up for themselves and not let that dude walk all over them.

MU

Have you had that experience at work, feeling walked all over?

AD

I stay out of their way. I just work. I don’t get involved with management usually. I just come in and get my check. And they just offered me a team lead job and everything. I was there every day and thought everything was cool. If I hadn’t posted the video, I would still be there working.

I had just come back from California in December. In January, I came back home because my son is here. He didn’t like me being gone — he had a hard time with it. So I decided to get something local, close to my dude. Because he loves me, you know what I mean?

MU

You said the workers walked off the job with their heads up.

AD

Yeah. It was powerful, bro. They were proud of themselves, like they’re supposed to be. But [management] still paid everybody for the whole day. That’s how you know they were wrong. They sent everybody home, but I stayed until the end, because I was in awe.

MU

Have you ever had an experience with that kind of action before?

AD

Never. It was like the Million Man March or something. You heard me in the video — I was excited.

MU

You’re black. The people you filmed in the video are Latino. You said in the description of your video that black people need to learn something from this. What did you mean?

AD

All the hate going on — we need to stick together. I think black people are moving in the right direction. We were down for a minute with the crack era. And you see the news, a lot of killings in the black community. Sometimes we don’t come together. But if they can do it, we can do it. And we can all come together. There’s power in numbers.

I don’t like racist anything. I don’t like people picking on people, bullying. It’s ridiculous. So when people come together, it’s a beautiful thing.

MU

They were specifically taking on a boss, taking action on the job.

AD

Yeah, and you can use that in any way. Votes, we could show up for. Or all corporations that have done you wrong.

We’re the ones, the workers — we make the heads get rich. Treating us lesser than isn’t even cool. We’re the reason the hub was getting built. Ain’t no owners out there in their hard hats. We’re the ones putting our life on the line. So you gotta respect us.

They’re a cool company. I don’t really have anything against them. But when you see wrong being done, you should step up and do something about it.

MU

There’s what was happening at your workplace, but then there’s the state of the economy as a whole.

AD

Yeah, and it can be on that scale. [The video] is funny or whatever, but people love seeing people come together like that. That’s why it’s so viral. Because everybody wants that deep down. Everybody wants to move as one. That’s why you look at the comments [on the video] and see black people saying, “Yeah, that’s what we need to do.”

MU

Do you think this experience will change you, on the job in the future?

AD

You can say that. It was life-changing to me to see that happen. Because it was like, dang, they really came together. And that’s why I’m not mad about the video, about getting fired. Because it’s five million people who saw that. And it might change their view on things. Empowering people.

So me losing a job is nothing compared to the big picture. If we can get it in our heads that we are the people, and if we make our numbers count, we can change anything.

Update: A GoFundMe has been created to support Dangerfield and his son.

- Source: JACOBIN

Spike Lee’s movie about a black cop infiltrating the KKK is a subtweet of Donald Trump

NEW YORK — Spike Lee has been opining for a few minutes now: Isn’t it ludicrous that people call football players unworthy of living in this country for kneeling during the national anthem, he says, when the first American who died during the Revolutionary War was a black man?

“So nobody can tell black people s— about going somewhere else,” he concludes. “Along with the genocide of Native Americans, this country got built cost-free from slavery.”

Seated on a bright purple couch in the Brooklyn office of his company, 40 Acres & a Mule Filmworks, Lee eventually pauses. It all comes down to love vs. hate, he says — it always has. That is why the two words appeared on the knuckle rings of Radio Raheem, a fictional character killed by police officers at the climax of Lee’s 1989 film “Do the Right Thing.” Some claim Lee is on a soapbox, but he really just wants to be on the loving side of history.

The provocative filmmaker, 61, has recently faced hurdles in his everlasting pursuit of this goal: “Da Sweet Blood of Jesus” opened to less-than-lukewarm applause in 2014, and the satirical depiction of violence in 2015’s “Chi-Raq” insulted some Chicago natives. But the latest Spike Lee joint, “BlacKkKlansman,” attempts to capture racial tension with the same clarity of “Do the Right Thing,” which Roger Ebert wrote came “closer to reflecting the current state of race relations in America than any other movie of our time.” Only this time, he attempts to do so using a story from the past.

“BlacKkKlansman,” which took home the Cannes Film Festival’s prestigious Grand Prix in May, tells the real-life story of a black Colorado Springs cop named Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) who infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan in the late 1970s by pretending to be a white man over the phone. But it also connects the Klan’s racism to what spurred last year’s Charlottesville rallies and even directly attacks the Trump administration for perpetuating such behavior.

Lee held such “precise opinions” throughout the project, co-writer Kevin Willmott says, that make today’s rant seem comparatively scattered. He frequently trails off in the middle of sentences, gazing off through his orange, thick-rimmed glasses. There is simply too much buzzing in his mind. From where he stands, hypocrisy among those in power, dubbed “snake oil salesman,” has reached an almost unfathomable level.

Although he refuses to utter the president’s name — “Who? Oh, Agent Orange” — Lee admits that while making “BlacKkKlansman,” “everything was done knowing that this guy had the nuclear code.” In one scene, Ron declares that the United States would never elect a man like KKK Grand Wizard David Duke (Topher Grace) president. A superior tells him he is remarkably naive for a black man.

“From the very beginning, Spike said, ‘I don’t want it to be a period piece,’” Willmott recalls. “He didn’t want to give people an out in terms of this being something from the olden days.”

News outlets disagree on whether the standing ovation “BlacKkKlansman” received at Cannes lasted for six or 10 minutes. Lee isn’t a numbers guy, so he doesn’t know which is accurate. What he does know, however, is what a relief it was to discover that the festival audience understood his film.

“It didn’t have to be that way,” he says. “People get booed at Cannes.”

They also get snubbed for awards, which Lee still holds happened to him back in 1989. He doesn’t have any beef with Steven Soderbergh, whose “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” beat front-runner “Do the Right Thing” for the Palme d’Or, or even the festival itself, but rather with the president of the jury: German filmmaker Wim Wenders.

Lee says jurors Sally Field and Hector Babenco later told him that Wenders overlooked “Do the Right Thing” because he considered Mookie, Lee’s protagonist who incites a riot after Radio Raheem’s death by throwing a garbage can through the window of a pizzeria, to be unheroic. The film ends with quotes from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, expressing their differing views on violence as self-defense against oppression.

By way of comparison, Lee exclaims, “If you look at the main character of ‘Sex, Lies, and Videotape,’ the guy was masturbating watching videotape.”

(Wenders responds in a statement, “It was an exceptionally great year in terms of films,” and adds, “I understood Spike’s frustration and even grief, and I was sorry that Spike concentrated his anger on me.”)

There is no denying the heroic qualities of Stallworth, played by Washington, son of Denzel. “The fruit doesn’t fall far from the tree,” Lee says of his natural talent. Washington spoke weekly with Stallworth, who swung by the set one day and passed around his KKK membership card, which Washington says “made it even more real and scarier.”

“Signed by Mr. Duke,” he adds, incredulous. “Are you kidding me? This is bananas.”

Patrice Dumas (Laura Harrier), an activist college student and Ron’s love interest, tells him in the movie that he “can’t change things from the inside. It’s a racist system.” Lee says he and Willmott wrote the line with W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness in mind: Ron is black, but, as a police officer, he also works a job with a history marred by violent racial oppression.

“It’s gotta be difficult for brothers and sisters who are police officers, because they’re not blind — they’ve gotta see what police forces are doing, shooting down black people left and right,” Lee says. “Knowing that black folks ain’t really feeling you, just because you’re black but you’re also a cop . . . in a lot of ways, Ron’s character is feeling that, too.”

Despite this inner turmoil, Ron orchestrates the undercover mission, persuading his colleague Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) to be his white stand-in at Klan meetings. He boldly calls up the KKK and proclaims to hate anyone who “doesn’t have pure white Aryan blood running through their veins.” He does so while working alongside a white officer who once shot a black child and continues to abuse his power.

“We’re flesh and blood, we feel everything,” Washington says. “But he had to just take it, approach it like a job so he didn’t crack.”

The actor/ director and producer says the warm reception at Cannes felt like winning the Super Bowl. But Lee still has the tiniest of bones to pick with this year’s jury president, Cate Blanchett, whom he says he loves dearly. After “BlacKkKlansman” won the Grand Prix, she described it as “quintessentially about an American crisis.”

The film does end with footage from last year’s neo-Nazi rallies in Charlottesville and President Trump’s response, but “this is not just America,” Lee counters. “It was happening in England, with Brexit. This right-wing thing is happening all over the world.”

A citrusy scent suddenly wafts through the office. Grapefruit, perhaps?

“Yeah, it’s a SoulCycle candle,” Lee says, resuming the calm demeanor that appears between his bursts of outrage. He is fresh off one about how the Trump administration’s shenanigans, skullduggery and subterfuge — “The three S’s!” as he repeatedly exclaims — will bring about the end of democracy as we know it.

It is in this even-keeled tone that Lee expresses how odd it is that people look to him for answers to the societal ills depicted in his films. But then he amps back up again, suggesting a solution anyway: To move forward, we must pursue the truth.

The pursuit requires taking off the rose-colored glasses through which we view our nation’s history, according to Lee, a product of the New York City public schools. That’s where he was taught the tale of George Washington cutting down a cherry tree.

“F— that,” Lee says. “George Washington owned slaves.”

He then directs the same profanity toward all of the Founding Fathers.

In interviews, the sheer strength of Lee’s emotions sometimes gets the better of him, such as when he said he had a “Louisville Slugger bat with Wenders’s name on it” in his closet. He once claimed that he could not have made an anti-Semitic film because Jews ran Hollywood, and “that’s a fact.”

His “25th Hour” star Edward Norton told the Atlantic years ago: “I don’t think Spike is his own best advocate. . . . People associate Spike sometimes with an angry righteousness and urgency that I don’t think his films have. I don’t think his films are angry at all. They are very compassionate.”

But Lee says he is always happy to do interviews — he did so as a young director when studios wouldn’t spend that much advertising money on his films and now does them as an artist passionate about his work’s message.

Lee has taken off his hat that says “BLACK” on the front, with a KKK hood in place of the A. “BlacKkKlansman” serves as a direct response to the “corn-fed American terrorism” that killed Heather Heyer as she protested Charlottesville’s white supremacist march and is set to hit theaters a few days before the one-year anniversary of her death. There is an urgency to this particular message, he says, Academy Awards season be damned.

David Duke says in the movie that he wants “America to achieve its greatness again.” Lee hopes American can achieve greatness, period.

READ MORE——-> THE WASHINGTON POST

He tried to break into a teen girl’s home because he wanted to ‘start a family,’ Tacoma police say

A man tried to break into a Tacoma home Wednesday because he wanted to “start a family with” a 13-year-old girl inside, Pierce County prosecutors allege.

The 27-year-old, whose address was not listed in court records, was arraigned Thursday in Superior Court. He faces charges of attempted residential burglary, communication with a minor for immoral purposes, obstructing police, lying to police and two counts of third-degree assault. Bail was set at $200,000.

According to charging documents:

A 13-year-old girl called police from her home on East 34th Street about 12:15 p.m. and said a man was trying to open the windows of her house.

“I want to date you,” the girl said he was calling from outside. “I want to start a family with you.”

Officers arrived to find the man in the backyard of the home. When he saw them, he fled but was captured nearby.

The 13-year-old told police she saw the man in a nearby church parking lot, where he could have seen into her bedroom. The man then removed a bungee cord from the fence, knocking down part of it.

The man approached the home and tried to open the back door, begging the teen to let him in. She called her father, who told her to call 911.

The man refused to give his name to police, instead telling officers to take him to jail. Once there, he spat on a Tacoma police officer. The officer tried to put a spit sock over the man’s head, which prompted the man to kick the officer.

Once inside, the man tried to sneak up on a corrections officer but was thwarted. He then lied about his name, and gave three different spellings of what his would-be alias was.

Officers eventually determined the man’s identity and discovered he had a warrant for his arrest.

READ MORE STORIES FROM THE TACOMA NEWS TRIBUNE

The gun’s not in the closet’

Since 1999, children have committed at least 145 school shootings. Among the 105 cases in which the weapon’s source was identified, 80 percent were taken from the child’s home or those of relatives or friends.

Yet The Washington Post found that just four adults have been convicted for failing to lock up the guns used.

Now, after a deadly school shooting in Kentucky, a prosecutor must decide: Should the parent who owned the weapon be charged?

The gunfire had lasted less than 10 seconds, but now hidden behind locked doors all across the rural campus, teenagers wept and bled and prayed.

Police would soon swarm Marshall County High’s hallways on that chilly morning in January, and though the exact number of students who had been shot remained unknown for hours, it didn’t take investigators long to find the boy they believed had pulled the trigger. His name was Gabriel Parker, a sophomore whose family lived near the banks of Kentucky Lake. Before word spread that two were dead and 14 were wounded, a detective headed south, in search of the answer to a question:

Where had Parker, who was 15, gotten the gun?

Beneath a wind chime topped with a metal cross, Parker’s stepfather, Justin Minyard, opened the front door of their modest frame house, and the detective told him what had just happened. The 26-year-old’s stepson, police alleged, had opened fire on hundreds of students gathered in Marshall’s commons with a Ruger 9mm semiautomatic pistol. Minyard, according to court records, acknowledged that he kept one firearm in the home, stored in his bedroom closet. He walked back and checked the shelf.

His gun, Minyard told the detective, was gone.

In the hours that followed, police say, Parker confessed to his interrogators that getting the weapon was easy. It hadn’t been secured with a lock or sealed in a safe or even hidden somewhere secret. The night before the shooting, Parker explained, he carried a laundry basket to his parents’ bedroom closet. He reached up to a shelf and grabbed the pistol, which was inside a case, then stuffed it beneath the clothes. Parker also took at least two magazines, along with the bullets he needed, leaving behind more than 400 rounds of ammunition that police would later seize. The next morning, he put the handgun in his bag and rode with his mom to the school of 1,400 students, where at 7:57 a.m., police said, he fired the first round.

Since 1999, the shooters in at least 145 acts of gun violence at primary and secondary schools have been under the age of 18, according to an analysis by The Washington Post. Discussions about how to curb shootings at American schools have centered on arming teachers or improving mental health treatment, banning military-style rifles or strengthening background checks. But if kids as young as 6 did not have access to guns, The Post’s findings show, two-thirds of school shootings over the past two decades could not have happened.

While investigators don’t always determine — or publicly reveal — the weapons’ origins, The Post found 105 cases in which the source was identified. Of those, the guns were taken from a child’s home or those of relatives or friends 84 times. The Post discovered just four instances when the adult owners of the weapons were criminally punished because they failed to lock them up.

When Commonwealth Attorney Mark Blankenship took on the Parker prosecution, his focus was solely on ensuring that the teen would be tried as an adult, making him eligible to receive a life sentence. But the longer Blankenship thought about how Parker had gotten the weapon, the more it troubled him.

Parker wasn’t a hunter and didn’t hang out much with the high schoolers who were. The teen, a plump redhead who wore glasses, was quiet and shy. He had a small group of friends, mostly from Marshall’s marching band, in which he played the tuba. The teen couldn’t have persuaded another student, or anyone else, to give him a weapon without raising considerable suspicion, Blankenship concluded. To the prosecutor, that meant the only gun Parker could have used to ravage his high school was the one he took from his stepfather’s closet.

Like almost everyone he knows, Blankenship, 65, owns a firearm. It’s a shotgun his father passed down to him, and though he doesn’t keep shells for it and has never considered himself an enthusiast, he’s been around guns since birth. Blankenship also appreciates why someone would want to reach a weapon quickly during a break-in, so he researched gun safes online, and what he found were more than a dozen devices for under $250 that had been designed to securely store pistols — just like Minyard’s — and be opened in less than three seconds.

“That’s when it really hit me,” Blankenship said, “that this was so easily preventable.”

Gun rights are revered in Marshall County, a community of 31,000 where 3 in 4 voters backed Donald Trump in 2016. Generations of cattle, corn and tobacco farmers throughout this nearly all-white swath of countryside have long viewed their rifles and shotguns much the same way they do their rakes and shovels: essential tools that, on their own, could do no harm. In fact, many people still find it more unseemly to drink a beer in public— Marshall was dry until 2015 — than to wield an AR-15 rifle in public — legal in almost all of Kentucky thanks to its open-carry law.

Blankenship, in office since 2008, was on the verge of beginning his reelection campaign and knew that scrutinizing the pistol’s owner would be unpopular, but he just couldn’t shake how much trauma one gun in the hand of one 15-year-old had caused.

There were the teachers who’d been covered in their own students’ blood, the officers whose kids were begging them not to go back to work, the paramedic who could no longer stand large crowds, the young siblings of high schoolers who imagined they would be shot next, the two couples who had outlived their children, and the teenagers — so many that Blankenship couldn’t fit everyone’s parents into his office — who had bullet holes in their arms and legs and chests and stomachs and faces.

So, about a week after the shooting, in a meeting with investigators, the prosecutor finally said it out loud: “I’m seriously thinking about going after the stepfather.”………

READ MORE WASHINGTON POST

Netflix Nappily Ever After Offical Trailer

Because the hypocrisy of it all I’m not with the whole natural hair movement but this movie sounds pretty good.

Cue the World’s Smallest Violin: White Driver Who Followed Black Man, Called Him Slurs, Now Whines About Life Being Ruined

Here is another racist bigot white boy with his white privilege who’s mouth wrote him a check he could not pay. As for me IDGAF! The only reason the white boy is saying he sorry is because he’s going to have to apply for welfare soon. Racism is bad for business we need to make an appointment to the doctor to get a prescription for some super strength kopetate for the diarrhea of his mouth.

An Ohio state contractor who, in a fit of road rage, took it upon himself to follow a black man to his home and call him a “nigger” repeatedly is now whining and complaining about his life being ruined.

Hmm, this year’s crop of white tears is exceptional.

Jeffrey Whitman, the owner of Uriahs Heating and Cooling, did all of this from behind of the wheel of his company truck, prompting immediate backlash and consequences. His image quickly spread online, his voicemail became full, his Yelp reviews were trashed and now he’s complaining.

“It was an awful mistake and obviously I don’t know how to explain it, and it’s ruined my life and it’s ruined my family’s life,” Whitman told the Columbus Dispatch.

“I’m out of business, I’m completely out, I’m done, I’ll never work in Columbus again,” he added. “This has completely and thoroughly ruined my life.”

Should have thought of that before you followed a black man some two miles to his house (like, what the fuck? This is how people get shot) and then called him racial slurs—neither action, by the way, really constitutes a mistake.

Whitman went viral last week after the victim, Charles Lovett, posted video of his encounter to Facebook.

The video shows Lovett getting out of his car and approaching a white commercial van sitting in front of his driveway. Lovett demands to know why the man followed him, only to be called a nigger.

“I just want to let you know what a nigger you’re being,” Whitman said.

“You want to let me know how much of a nigger I am?” Lovett cooly replied.

“Yeah, I want to let you personally know how much of a nigger you are,” the contractor continued.

At first, Whitman pretended he could square up, refusing to apologize, insisting he didn’t follow Lovett (even though he ended up in the man’s driveway,) and saying that the n-word wasn’t a big deal because he grew up with it.

After the backlash began, he began to sing a more humble tune and issued an apology, but it was too little too late.

But, get this, even after all of this, Whitman is still insisting he’s not racist and saying that he doesn’t know why there’s so much hate. The cognitive dissonance.

“I just don’t understand the intensity of the hate,” he said.

“I was just trying to address the rudeness,” Whitman added, apparently refusing to see the irony of addressing rudeness by calling someone not only a name but a fucking slur.

Ah, well. Dun, dun, dun, dun, another one bites the dust.

READ MORE FROM THE ROOT