New Documentary to Shed Light on Why Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing ta F’ Wit

(L-R) Masta Killa, Ghostface Killah, RZA, Method Man, GZA, (front) Raekwon and Cappadonna of Wu Tang Clan attends the Mtn Dew ICE launch event on January 18, 2018 in Brooklyn, New York. Photo: Dimitrios Kambouris (Getty Images for Mountain Dew)

Cinematographer Hans Charles wanted to visually frame the Wu-Tang Clan and all of their personas in a way that celebrated each of them as thriving black men in America. Likewise, director Sacha Jenkins understood that the real story in their four-hour documentary on Wu-Tang’s music and legacy is really about “black men who knew each other as boys coming together and using their creativity to overcome the madness they faced growing into young men,” Jenkins said.

In an exclusive interview with The Root, the pair shared that their collaboration will result in the most comprehensive, visual story to date of the Clan with a new, as yet untitled documentary that’s due out next year.

“Rappers who have been able to make it, who have been consistent, managed the height of their career and still manage a career after hit records and have cultural influence are genuinely smart people,” said Charles about Wu Tang, “We tend to overlook that about them and think it’s just luck.”

Wu-Tang—whose original members included RZA, GZA, Raekwon, Method Man, Ghostface Killah, Inspectah Deck, Masta Killa, U-God and the late, great Ol’ Dirty Bastard—may be the one of the few rap group from the early ’90s who still tours and brings an inter-generational excitement to everything they touch. The group spawned all kinds of ancillary Wu-related content—including books like The Wu-Tang Manual, the Wu-Wear fashion line, The Nine Rings of Wu-Tang comic book series, not to mention the countless solo albums from individual members and affiliate members like the Killa Beez. RZA and GZA even kicked it in a movie with Bill Murray.

For Charles and Jenkins, telling Wu-Tang’s story is partly telling their own hip-hop story. Charles grew up in Connecticut listening to New York radio. Since then, he has shot for Spike Lee and, most recently, for a critically acclaimed documentary on Ellis Haizlip and the groundbreaking PBS show, Soul! He was nominated for an Emmy for his cinematography for Ava DuVernay’s 13th and has his first feature film, I Angry Black Man, coming out next year.

For Jenkins the connections are even more personal. He published the first cover story on the group in 1992, before anyone knew them, for his startup newspaper, Beat Down. He has since produced documentaries on hip-hop—Fresh Dressed, about the mainstreaming of hip-hop fashion, and Showtime’s Word is Bond, about hip-hop’s Bronx-born history.

Charles’ and Jenkins’ collaboration on Wu-Tang is a comprehensive history culled from exhaustive interviews with every member of the group, family members and archival footage.

“We really went in,” said Charles. “Their story origin in and of itself is so fascinating and so layered.”

That origin story begins in Staten Island, the forgotten borough of New York, and a character itself in the film.

“There’s no way you can talk about Wu Tang without talking about the importance of Staten Island,” said Charles. “We walked the hallways where they grew up. You’ll be surprised when the brothers talk about how it shaped them and what it meant to them.”

Jenkins agrees, adding, “A lot of their mothers migrated from Brooklyn because they heard it was a better quality of life. Eventually they discovered that all the things they were trying to escape in Brooklyn followed them to Staten Island.

“They were unabashedly from the projects, and not changing who they were to fit in or to entertain people. They were talking about their lives and what they were up against and people found it relatable,” said Jenkins. Their unfiltered rawness, quirky hobbies and obsessions, and Five Percent-inspired philosophies resonated with people from all walks of life. “We listened to Wu-Tang to survive private school, in college they got us through,” said Charles. “They were helping the black nerds, too.”

At the Anthem in Washington, D.C., earlier this month, the now 10-member Clan (longtime collaborator Cappadonna became an official member in 2007) came together for their reunion tour to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), with Redman, another longtime collaborator, as the opening act. ODB was replaced by his son, the Young Dirty Bastard, who is the spitting image of his father, down to the comic and manic shimmy, shimmy ya ya-ing across the stage with all of the mannerisms of his father. Raekwon, now a wine connoisseur, has a little more weight around his mid-section, and GZA, a vegan now, has a little less hair, but they still brought the same energy to their stage show that always ends with fifty-eleven people onstage.

The crowd, many dressed in Wu-Wear, featured everybody from white people from the cornfields of Iowa to elderly couples, wanna-be-thugs and actual thugs. The eclectic crowd was just more proof that with RZA as the philosophical leader, the group continues to have a profound worldwide cultural impact.

“Wu Tang for many people around the world was their introduction to hip hop. Around the world they don’t see Wu Tang as a rap group, they see them as embodying the essence of what hip hop really is,” said Jenkins.

READ MORE FROM THE ROOT

Meet Skull Snaps A Forgotten Funk Band That Soundtracked Hip-Hop

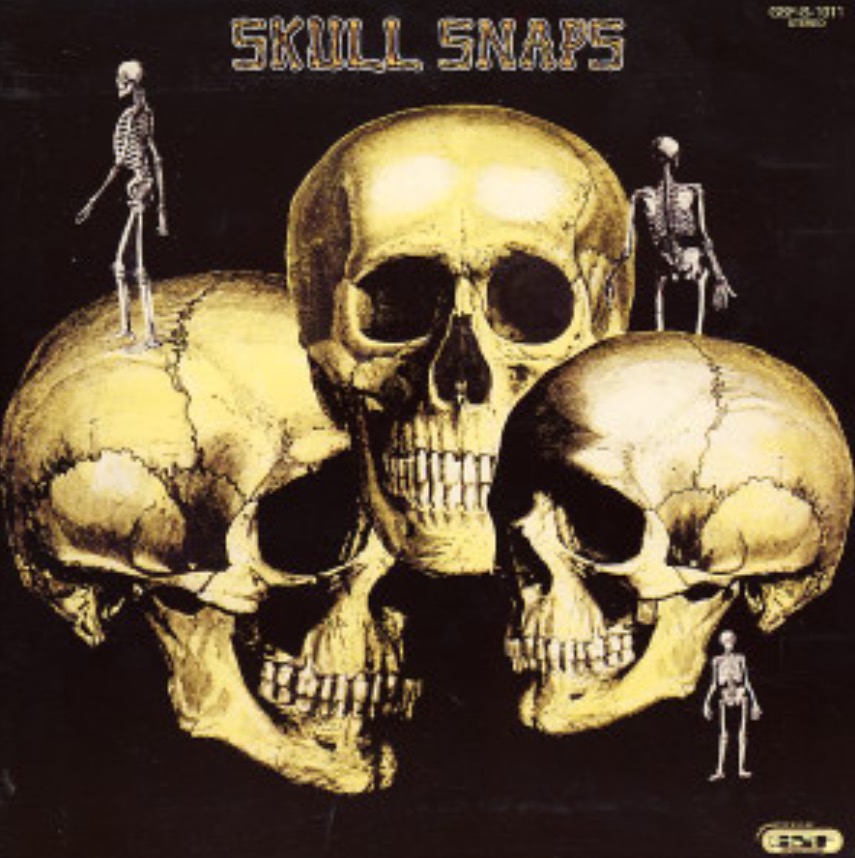

Skull Snaps

New Haven, Connecticut rapper Dooley-O and DJ Chris Cosby were digging through a neighbor’s record collection when they found a peculiar album, the cover of which boasted a drawing of three menacing skulls, with skeletons dancing on or near each one. The back cover had an image of a presumably female skeleton, wearing a fancy Victorian hat. The band was called Skull Snaps, and there was no photo of the artists anywhere to be found.

Dooley-O assumed this was a heavy rock album, and since he was a crate-digger who happily sampled any and everything, he decided to give it a listen. As it turned out, the album wasn’t rock, but funk—one song in particular, “It’s a New Day,” boasted a killer opening beat that was just begging to be sampled. And so, in 1988, Dooley-O did just that on a track called “Watch My Moves,” but since he didn’t have any industry connections that could help promote the song, it languished in semi-obscurity. (It was eventually released 14 years later by Stones Throw Records.)

One year after Dooley-O recorded “Watch My Moves,” his cousin Stezo, who’d gotten a gig as a backup dancer for EPMD, scored a record deal and asked Dooley if he could use the Skull Snaps break. Dooley didn’t like the idea at first, but he eventually relented. Stezo’s song, “It’s My Turn,” went big, reaching Number 18 on Billboard’s “Hot Rap Songs” chart.

That was only the beginning. Since Stezo let the sample play out naked in the song, it quickly became fodder for hundreds of other rappers. It now appears on nearly 500 songs, making it one of the most sampled breaks in hip-hop history.

“That thing sounds good. You can put any kind of groove to that and it sounds good. Any groove,” Stezo says today. “I remember Dooley being like, ‘Don’t leave the beat open because people are going to steal our beat.’ I said, ‘Man, what do we care about, as long as we’re the first ones.’”

That Skull Snaps break was sampled on a host of prominent rap songs—among them, the Pharcyde’s “Passing Me By,” Mobb Deep’s “Give Up The Goods (Just Step),” and Gang Starr’s “Take It Personal”—but even at the height of its usage, few people knew anything about Skull Snaps.

All of that is about to change. In 2011 and ‘12, Stezo shot a documentary about the group in 2011-2012 called The Birth Beats of Hip-hop: The Legend of Skull Snaps. And in October, Mr. Bongo reissued Skull Snaps on vinyl with support from band members themselves. As it turns out, Skull Snaps were a three-piece band consisting of Sam O. Culley, Erv Littleton Waters, and George Bragg. The members were also in soul group called The Diplomats, who released a number of singles in the ’60s. As for the album’s mysterious cover, Culley says it wasn’t intended to misdirect people. The band had a tough time being a funk trio who played their own instruments and did all their own singing, and funk and soul labels just didn’t know how to market them.

“My favorite artist was Three Dog Night. Record companies weren’t really accepting black bands back then,” Culley explains. “So we said, ‘We’ll have no pictures on the album. The guy who did the artwork put the three skeletons on top of the damned skull and I’m like, ‘Damn that’s crazy looking. It’s the scariest shit I’ve ever seen.’ It made me think of bikers. That was my first thought. They’re going to think this is a bunch of bikers, you know what I’m saying?”

That strange record cover would likely have never come to pass without the group’s unusual name, which was inspired by R&B vocalist Lloyd Price. One night, Price was hanging out with the group and enthusing over their funky sounds. During one session, he blurted out that their music “made his skull snap.”

The Skull Snaps record was released in 1973, but the famous beat that would inspire a generation of rappers goes back to the mid ’60s, when the band members would play it at the beginning of shows as a way of getting the energy going. The unique sound and pop of the beat was made by taking a small 12-inch snare and dampening its sound by taping a wallet to it.

“It basically was a tune-up kind of thing,” Culley says. “The drums started playing, and I would start playing on the bass, and then Erv started playing on the guitar, and from that, we would just bam to another song which would be our show.”

That Skull Snaps break was sampled on a host of prominent rap songs—among them, the Pharcyde’s “Passing Me By,” Mobb Deep’s “Give Up The Goods (Just Step),” and Gang Starr’s “Take It Personal”—but even at the height of its usage, few people knew anything about Skull Snaps.

All of that is about to change. In 2011 and ‘12, Stezo shot a documentary about the group in 2011-2012 called The Birth Beats of Hip-hop: The Legend of Skull Snaps. And in October, Mr. Bongo reissued Skull Snaps on vinyl with support from band members themselves. As it turns out, Skull Snaps were a three-piece band consisting of Sam O. Culley, Erv Littleton Waters, and George Bragg. The members were also in soul group called The Diplomats, who released a number of singles in the ’60s. As for the album’s mysterious cover, Culley says it wasn’t intended to misdirect people. The band had a tough time being a funk trio who played their own instruments and did all their own singing, and funk and soul labels just didn’t know how to market them.

“My favorite artist was Three Dog Night. Record companies weren’t really accepting black bands back then,” Culley explains. “So we said, ‘We’ll have no pictures on the album. The guy who did the artwork put the three skeletons on top of the damned skull and I’m like, ‘Damn that’s crazy looking. It’s the scariest shit I’ve ever seen.’ It made me think of bikers. That was my first thought. They’re going to think this is a bunch of bikers, you know what I’m saying?”

That strange record cover would likely have never come to pass without the group’s unusual name, which was inspired by R&B vocalist Lloyd Price. One night, Price was hanging out with the group and enthusing over their funky sounds. During one session, he blurted out that their music “made his skull snap.”

The Skull Snaps record was released in 1973, but the famous beat that would inspire a generation of rappers goes back to the mid ’60s, when the band members would play it at the beginning of shows as a way of getting the energy going. The unique sound and pop of the beat was made by taking a small 12-inch snare and dampening its sound by taping a wallet to it.

“It basically was a tune-up kind of thing,” Culley says. “The drums started playing, and I would start playing on the bass, and then Erv started playing on the guitar, and from that, we would just bam to another song which would be our show.”

When it came time to record the Skull Snaps record, they felt that jam needed to be included somewhere. They decided to append it to the beginning of “It’s a Brand New Day” because that was the first song they recorded. Just like in their live shows, they needed the beat to help them get calibrated in the studio.

“We said, ‘We can’t leave that out, because we know what that does to us mentally. It makes us tight, it pulls us right together,’” Culley says. “Once we started the beat like that and we had put vocal arrangement on ‘It’s a New Day,’ it was almost a surprise that the damn thing sounded the way it did, because we have never heard how it sound recorded.”

That beat, like much of the record, was a one-take situation. Just like that, unbeknownst to them, an important piece of hip-hop history was born.

Unlike a lot of rediscovered ’70s soul/funk gems, Skull Snaps clearly sounds like it could have been a hit in its own time. The album strikes the perfect balance of heartbreaking ballads, uptempo soul songs, and gritty funk jams, all of them boasting impressive vocal harmonies.

“We said we were going to do every kind of song on the album. That’s what we set out to do, and that’s what we did,” Culley says. “Each one of us could sing lead. That made it even better, so when you switch off on different things, no one is not more powerful than the other.”

In the end, the strange album cover and lack of band photo probably didn’t help the band in their quest for stardom. But the biggest problem they faced was the fact that, just six months after releasing the record, their label GSF went belly up and completely disappeared, leaving the band in the lurch. The musicians were experienced, but they had hardly ever gigged under the name Skull Snaps.

“I can count the gigs on one hand that we did [under that name],” Culley says. “We were still using the name Diplomats, and we were all over the place. But they didn’t know it was Skull Snaps. And because we didn’t know what the record was going to do and once the company folded, we sort of pulled back on it.”

The members of the group have continued to write and record new music, and are gearing up to release a whole new Skull Snaps record sometime in 2019.

“It’s going to be different kinds of music—the same setup as the first album,” Culley says. “Very diverse, you know what I mean. It’s going to be really nice. I’m really appreciative of that fact that it’s happening now, and the idea that we’re still around and we’re still recording. We’re still in the business.”

Stezo and Culley are still in contact and talk regularly. Stezo hopes his documentary brings more awareness to who Skulls Snaps are as people and how talented they are. And he’s hoping most of all that the hip-hop community pay their respects. While shooting the documentary, he introduced the band to several rappers who had sampled the break for their own songs.

“Immediately everyone’s thoughts went to, ‘Oh my God, they’re here to sue us,’” Culley says. “But they found out it was just the opposite. We wanted to meet those people who had used that sample,” Culley says. “All of them were like, ‘You know how many careers you saved, how many lives you saved with that breakbeat?’ That’s amazing. And they’re still using it.”

Stezo, on the other hand, thinks that some of these rappers, particularly the more famous ones, should do the honorable thing and cut Skulls Snaps a check.

“They live. They’re here. They’re healthy. Talk to them now while they can enjoy the money. Not when they’re gone,” Stezo says. “I heard it on Fresh Prince of Bel-Air one time. Jazzy Jeff was cutting it up while Will Smith was dancing. It was crazy. Where the fuck is Skull Snaps’ money? That was my mission. I’m still on that mission.”

Orginal article from BANDCAMP DAILY

St. Louis Cops Giddily Planned to Beat Protesters but Unwittingly Beat an Undercover Cop. Now They’re Indicted

The aftermath of Jason Stockley’s acquittal for the killing of Anthony Lamar Smith carried an electric, emotional charge for members of the St. Louis community—but it was about to be an event for a few St. Louis Metropolitan Police officers.

According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, three officers, Dustin Boone, Randy Hays, and Christopher Myers, brutally beat a protester at an action a couple days after the Sept. 15, 2017, verdict. Though the protester complied with instructions, the officers inflicted heavy damage with kicks and a riot baton. What they didn’t realize: The man was a 22-year veteran cop, since speculated by the Post-Dispatch to be Luther Hall, who was undercover.

Hall was kicked in the face, which inflamed his jaw muscles to the point where he could not eat. He went from about 185 pounds to 165.

The cut above his lip was a 2-centimeter hole that went through his face.

He also sustained an injury to his tailbone, which still causes him pain, the sources said.

What makes it even worse: These officers had been excited to do damage like this the whole day.

From the Washington Post:

“It’s gonna get IGNORANT tonight!!” [Boone] texted on Sept. 15, 2017, the day of the verdict. “It’s gonna be a lot of fun beating the hell out of these s—-heads once the sun goes down and nobody can tell us apart!!!!”

It’s already terrifying what people will do under the veil of anonymity; holding police accountable is already an uphill battle with full uniforms, bodycams, and eyewitnesses. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that officers might abuse their posts when they feel they’re even less liable to be caught.

The evidence is damning. Another officer, Bailey Colletta, has been charged for lying to a federal grand jury. We know how easy it is for police to lie on each other’s behalf. What will happen now that the victim is an officer, too? No bets, but we know black officers sometimes face a special sort of danger.

I always pose these hypotheticals with a tinge of pessimism, and now is no different: Would there have been consequences if the undercover officer had been a civilian? (Likely not.) I’d like to think Hall’s life would have mattered had he not been a police officer, but reality has proved me wrong over and over.

Correction: 11/30/2018, 3:14 p.m. EDT: A typo listed Luther Hunt as a 22-year-old officer when he is not 22 and has in fact been on the police force for 22 years. It has been corrected above.

READ MORE FROM THE ROOT