From 13,000 in Tacoma to 100 million nationwide needle exchange proves worth over 30 years

Rebecca Ford remembers keeping $500 in bail money in her freezer, just in case.

Ford’s father, the late Dave Purchase, is widely regarded as not just the father of syringe exchange in Tacoma and Pierce County but across the nation. This week, the program Purchase started celebrated its 30th anniversary.

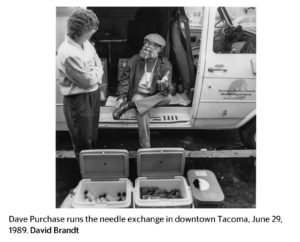

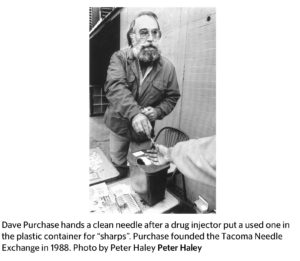

Back in 1988, however, when Purchase famously set up his television tray and folding chair downtown and started handing out clean needles to individuals battling intravenous-drug addiction, he was breaking new ground, breaking down barriers and stereotypes — and potentially breaking the law.

While Purchase had secured the support of Tacoma Police Chief Ray Fjetland, who agreed to suspend the enforcement of local paraphernalia laws to give Purchase’s idea a chance to succeed, the early incarnation of what would soon become the first legally sanctioned and publicly funded needle exchange in the country was fraught with legal risk for the man behind it.

“The public just thought it was his way of promoting drug use, and promoting everything that people are afraid of — drug use, and drug users,” Ford, now 56, said. “The general public thought it was an annihilation of their town. Even though there was this problem in Tacoma, it just was ignored, and he just knew people were dying.”

The problem was the HIV and AIDS epidemic, and back in 1988 it was building to a crescendo.

According to the statistics from the Centers for Disease Control at the time, by December 1988 there had been nearly 83,000 cases of AIDS reported across the country.

A year later, in December 1989, that number would reach nearly 118,000.

By December 2000, the number would climb to 774,467, with 448,060 confirmed deaths.

That’s why Purchase, a Stadium High School grad with the beard of a biker and the rare ability to navigate both the halls of bureaucracy and the back alleys where those in the depths of addiction often congregated, took it upon himself to act when he did.

In short order, those efforts would lead to the creation of the Point Defiance AIDS Project — which is now an umbrella organization for the Tacoma Needle Exchange, and the nonprofit North American Needle Exchange Network (NASEN). From its inconspicuous office on Dock Street, NASEN helps provide guidance, expertise and millions of needles every year to syringe exchange programs in the United States, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

According to Dr. Don Des Jarlais, a professor of epidemiology at the NYU College of Global Public Health, there are about 300 needle exchange programs across the country. In the world of public health, needle exchange programs are widely regarded as an effective way to prevent the spread of infectious diseases amongst IV drug users.

Des Jarlais, who traveled to Tacoma to study the impacts of Purchase’s program in its early stages, says much of the credit for the proliferation and acceptance of needle exchange programs goes to Purchase, who died in 2013.

In Purchase’s obituary, published in The New York Times, Des Jarlais said, “The efforts of Dave and people like him have literally saved hundreds of thousands of lives.”

“(Purchase) was really the driving force, more than anyone else, in terms of expanding syringe exchange throughout the country,” DesJarlais said today.

The point is the point

Today, according to Des Jarlais, there is virtually no scientific debate about the effectiveness or importance of syringe programs.

“Within the public health community, syringe exchange is just totally accepted and supported as a necessary measure for dealing with injecting drug use,” Des Jarlais said. “Certainly within the public health field, syringe exchange is seen as absolutely critical.”

It’s a stark contrast from the climate Purchase had to navigate when he started Tacoma’s syringe exchange program.

At the time, Purchase, who had a history as a drug counselor, was alarmed by the number of individuals he regularly interacted with on the job being stricken by HIV and AIDS. After he was involved in a serious motorcycle accident — hit by a drunk driver — the long recovery process gave him time to think about a way to respond.

Eventually, Purchase used money from the insurance settlement he received to start his fledgling needle exchange program, which as the New York Times documented in 1989, started by distributing clean needles along with “condoms, bottles of bleach and alcohol swabs.”

As The New York Times reported, Purchase handed out 13,000 needles in his first five months on the street.

Perhaps even more impressive, the effort quickly earned the support of not just the local police chief, but the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department, which by 1989 was helping to fund the program.

Terry Reid remembers it well. At the time, Reid managed the county’s AIDS and substance abuse programs. Now retired, he looks back on helping Purchase’s needle exchange program get off the ground and calls it “the highlight of my 35 years in public health.”

Of course, the success didn’t come without challenges, and winning support wasn’t always easy. While Reid recalls the “ground being softened” at the health department, thanks to previous street outreach and HIV prevention efforts, the idea of distributing clean needles to IV drug users was still highly controversial and politically charged.

“There was definitely a majority of people who were against needle exchange,” Reid said. “I’ll bet it would have been 70 percent against it (in a public poll).

Still, community unease didn’t stop Purchase and the ardent group of supporters he’d attracted along the way, including Reid, then-County Councilman Dennis Flannigan and Lyle Quasim, who worked as the state director of mental health and later with Safe Streets, from persisting.

“I had seen one of the methadone treatment clients with AIDS, who had transferred from a San Francisco program and literally withered away and died in our program,” Reid said. “I was also plugged in to some of the research taking place on the East Coast, particularly New York, where the number of AIDS cases were just exploding relating to IV drug use.

“I thought, ‘My god, we’re in a position where we could do something about that.”

So Reid agreed to help.

“It was an opportunity, and fortunately I was sort of in the right place, and brave enough — and careless enough with my career — to forge ahead,” he said. “It just seemed like the right thing to do.”

Challenges to the program have been a near constant throughout its three decades. Nearly seven years after it began, then City Councilman Steve Kirby spearheaded an effort to try to drive it out of Tacoma.

As The News Tribune’s Barbara Clements and Elaine Porterfield reported in 1995, Kirby’s crusade struck themes that were surely familiar to Purchase — arguing that syringe exchange promoted crime and condoned illegal drug use.

“I don’t believe we should be handing out needles to addicts,” Kirby told The News Tribune 23 years ago. “I think we ought to be arresting them and getting them off the street.”

Reached this week, Kirby couldn’t help but chuckle when presented with his past bluster. In many ways, Kirby’s evolution is indicative of the way society’s perception of needle exchange and preventative public health have changed over the years.

“Those were times when I was quite the big crime fighter and neighborhood activist. I would do whatever it took to defend my neighborhood and neighborhoods throughout Tacoma,” Kirby said, acknowledging that there was likely some political posturing behind his remarks from the time.

“I would not be surprised I that’s exactly what I said. If you guys wrote it, it was true” Kirby continued. “For the record, if I ever believed that, I don’t believe it now. I think it’s a dumb idea to arrest drug addicts and throw them in jail.

“I haven’t heard a complaint about the needle exchange in I don’t even know how long — decades.”

Quasim also can’t help but be surprised by what the effort accomplished, and the societal shift it helped inspire.

“The environment, on a scale to 1 to 10, the sympathy in our community was maybe running around a 2 or 3 at best. People really seemed to have their minds made up about (AIDS) being a disease that was the fault of the person who had it, or that they’d engaged in nefarious behavior and it was punishment,” Quasim recently recalled.

While Purchase had secured the support of Tacoma Police Chief Ray Fjetland, who agreed to suspend the enforcement of local paraphernalia laws to give Purchase’s idea a chance to succeed, the early incarnation of what would soon become the first legally sanctioned and publicly funded needle exchange in the country was fraught with legal risk for the man behind it.

Hence the stack of cash in his daughter’s freezer.

Just in case.

“The public just thought it was his way of promoting drug use, and promoting everything that people are afraid of — drug use, and drug users,” Ford, now 56, said. “The general public thought it was an annihilation of their town. Even though there was this problem in Tacoma, it just was ignored, and he just knew people were dying.”

The problem was the HIV and AIDS epidemic, and back in 1988 it was building to a crescendo.

According to the statistics from the Centers for Disease Control at the time, by December 1988 there had been nearly 83,000 cases of AIDS reported across the country.

A year later, in December 1989, that number would reach nearly 118,000.

By December 2000, the number would climb to 774,467, with 448,060 confirmed deaths.

That’s why Purchase, a Stadium High School grad with the beard of a biker and the rare ability to navigate both the halls of bureaucracy and the back alleys where those in the depths of addiction often congregated, took it upon himself to act when he did.

In short order, those efforts would lead to the creation of the Point Defiance AIDS Project — which is now an umbrella organization for the Tacoma Needle Exchange, and the nonprofit North American Needle Exchange Network (NASEN). From its inconspicuous office on Dock Street, NASEN helps provide guidance, expertise and millions of needles every year to syringe exchange programs in the United States, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

According to Dr. Don Des Jarlais, a professor of epidemiology at the NYU College of Global Public Health, there are about 300 needle exchange programs across the country. In the world of public health, needle exchange programs are widely regarded as an effective way to prevent the spread of infectious diseases amongst IV drug users.

Des Jarlais, who traveled to Tacoma to study the impacts of Purchase’s program in its early stages, says much of the credit for the proliferation and acceptance of needle exchange programs goes to Purchase, who died in 2013.

In Purchase’s obituary, published in The New York Times, Des Jarlais said, “The efforts of Dave and people like him have literally saved hundreds of thousands of lives.”

“(Purchase) was really the driving force, more than anyone else, in terms of expanding syringe exchange throughout the country,” DesJarlais said today.

The point is the point

Today, according to Des Jarlais, there is virtually no scientific debate about the effectiveness or importance of syringe programs.

“Within the public health community, syringe exchange is just totally accepted and supported as a necessary measure for dealing with injecting drug use,” Des Jarlais said. “Certainly within the public health field, syringe exchange is seen as absolutely critical.”

It’s a stark contrast from the climate Purchase had to navigate when he started Tacoma’s syringe exchange program.

At the time, Purchase, who had a history as a drug counselor, was alarmed by the number of individuals he regularly interacted with on the job being stricken by HIV and AIDS. After he was involved in a serious motorcycle accident — hit by a drunk driver — the long recovery process gave him time to think about a way to respond.

Eventually, Purchase used money from the insurance settlement he received to start his fledgling needle exchange program, which as the New York Times documented in 1989, started by distributing clean needles along with “condoms, bottles of bleach and alcohol swabs.”

As The New York Times reported, Purchase handed out 13,000 needles in his first five months on the street.

Perhaps even more impressive, the effort quickly earned the support of not just the local police chief, but the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department, which by 1989 was helping to fund the program.

Terry Reid remembers it well. At the time, Reid managed the county’s AIDS and substance abuse programs. Now retired, he looks back on helping Purchase’s needle exchange program get off the ground and calls it “the highlight of my 35 years in public health.”

Of course, the success didn’t come without challenges, and winning support wasn’t always easy. While Reid recalls the “ground being softened” at the health department, thanks to previous street outreach and HIV prevention efforts, the idea of distributing clean needles to IV drug users was still highly controversial and politically charged.

“There was definitely a majority of people who were against needle exchange,” Reid said. “I’ll bet it would have been 70 percent against it (in a public poll).

Still, community unease didn’t stop Purchase and the ardent group of supporters he’d attracted along the way, including Reid, then-County Councilman Dennis Flannigan and Lyle Quasim, who worked as the state director of mental health and later with Safe Streets, from persisting.

“I had seen one of the methadone treatment clients with AIDS, who had transferred from a San Francisco program and literally withered away and died in our program,” Reid said. “I was also plugged in to some of the research taking place on the East Coast, particularly New York, where the number of AIDS cases were just exploding relating to IV drug use.

“I thought, ‘My god, we’re in a position where we could do something about that.”

So Reid agreed to help.

“It was an opportunity, and fortunately I was sort of in the right place, and brave enough — and careless enough with my career — to forge ahead,” he said. “It just seemed like the right thing to do.”

Challenges to the program have been a near constant throughout its three decades. Nearly seven years after it began, then City Councilman Steve Kirby spearheaded an effort to try to drive it out of Tacoma.

As The News Tribune’s Barbara Clements and Elaine Porterfield reported in 1995, Kirby’s crusade struck themes that were surely familiar to Purchase — arguing that syringe exchange promoted crime and condoned illegal drug use.

“I don’t believe we should be handing out needles to addicts,” Kirby told The News Tribune 23 years ago. “I think we ought to be arresting them and getting them off the street.”

Reached this week, Kirby couldn’t help but chuckle when presented with his past bluster. In many ways, Kirby’s evolution is indicative of the way society’s perception of needle exchange and preventative public health have changed over the years.

“Those were times when I was quite the big crime fighter and neighborhood activist. I would do whatever it took to defend my neighborhood and neighborhoods throughout Tacoma,” Kirby said, acknowledging that there was likely some political posturing behind his remarks from the time.

“I would not be surprised I that’s exactly what I said. If you guys wrote it, it was true” Kirby continued. “For the record, if I ever believed that, I don’t believe it now. I think it’s a dumb idea to arrest drug addicts and throw them in jail.

“I haven’t heard a complaint about the needle exchange in I don’t even know how long — decades.”

Quasim also can’t help but be surprised by what the effort accomplished, and the societal shift it helped inspire.

“The environment, on a scale to 1 to 10, the sympathy in our community was maybe running around a 2 or 3 at best. People really seemed to have their minds made up about (AIDS) being a disease that was the fault of the person who had it, or that they’d engaged in nefarious behavior and it was punishment,” Quasim recently recalled.

Rebecca Ford remembers keeping $500 in bail money in her freezer, just in case.

Ford’s father, the late Dave Purchase, is widely regarded as not just the father of syringe exchange in Tacoma and Pierce County but across the nation. This week, the program Purchase started celebrated its 30th anniversary.

Back in 1988, however, when Purchase famously set up his television tray and folding chair downtown and started handing out clean needles to individuals battling intravenous-drug addiction, he was breaking new ground, breaking down barriers and stereotypes — and potentially breaking the law.

ADVERTISING

inRead invented by Teads

While Purchase had secured the support of Tacoma Police Chief Ray Fjetland, who agreed to suspend the enforcement of local paraphernalia laws to give Purchase’s idea a chance to succeed, the early incarnation of what would soon become the first legally sanctioned and publicly funded needle exchange in the country was fraught with legal risk for the man behind it.

Hence the stack of cash in his daughter’s freezer.

Just in case.

“The public just thought it was his way of promoting drug use, and promoting everything that people are afraid of — drug use, and drug users,” Ford, now 56, said. “The general public thought it was an annihilation of their town. Even though there was this problem in Tacoma, it just was ignored, and he just knew people were dying.”

The problem was the HIV and AIDS epidemic, and back in 1988 it was building to a crescendo.

According to the statistics from the Centers for Disease Control at the time, by December 1988 there had been nearly 83,000 cases of AIDS reported across the country.

A year later, in December 1989, that number would reach nearly 118,000.

By December 2000, the number would climb to 774,467, with 448,060 confirmed deaths.

That’s why Purchase, a Stadium High School grad with the beard of a biker and the rare ability to navigate both the halls of bureaucracy and the back alleys where those in the depths of addiction often congregated, took it upon himself to act when he did.

In short order, those efforts would lead to the creation of the Point Defiance AIDS Project — which is now an umbrella organization for the Tacoma Needle Exchange, and the nonprofit North American Needle Exchange Network (NASEN). From its inconspicuous office on Dock Street, NASEN helps provide guidance, expertise and millions of needles every year to syringe exchange programs in the United States, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

According to Dr. Don Des Jarlais, a professor of epidemiology at the NYU College of Global Public Health, there are about 300 needle exchange programs across the country. In the world of public health, needle exchange programs are widely regarded as an effective way to prevent the spread of infectious diseases amongst IV drug users.

Des Jarlais, who traveled to Tacoma to study the impacts of Purchase’s program in its early stages, says much of the credit for the proliferation and acceptance of needle exchange programs goes to Purchase, who died in 2013.

In Purchase’s obituary, published in The New York Times, Des Jarlais said, “The efforts of Dave and people like him have literally saved hundreds of thousands of lives.”

“(Purchase) was really the driving force, more than anyone else, in terms of expanding syringe exchange throughout the country,” DesJarlais said today.

The point is the point

Today, according to Des Jarlais, there is virtually no scientific debate about the effectiveness or importance of syringe programs.

“Within the public health community, syringe exchange is just totally accepted and supported as a necessary measure for dealing with injecting drug use,” Des Jarlais said. “Certainly within the public health field, syringe exchange is seen as absolutely critical.”

It’s a stark contrast from the climate Purchase had to navigate when he started Tacoma’s syringe exchange program.

At the time, Purchase, who had a history as a drug counselor, was alarmed by the number of individuals he regularly interacted with on the job being stricken by HIV and AIDS. After he was involved in a serious motorcycle accident — hit by a drunk driver — the long recovery process gave him time to think about a way to respond.

Eventually, Purchase used money from the insurance settlement he received to start his fledgling needle exchange program, which as the New York Times documented in 1989, started by distributing clean needles along with “condoms, bottles of bleach and alcohol swabs.”

As The New York Times reported, Purchase handed out 13,000 needles in his first five months on the street.

Perhaps even more impressive, the effort quickly earned the support of not just the local police chief, but the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department, which by 1989 was helping to fund the program.

Terry Reid remembers it well. At the time, Reid managed the county’s AIDS and substance abuse programs. Now retired, he looks back on helping Purchase’s needle exchange program get off the ground and calls it “the highlight of my 35 years in public health.”

Of course, the success didn’t come without challenges, and winning support wasn’t always easy. While Reid recalls the “ground being softened” at the health department, thanks to previous street outreach and HIV prevention efforts, the idea of distributing clean needles to IV drug users was still highly controversial and politically charged.

“There was definitely a majority of people who were against needle exchange,” Reid said. “I’ll bet it would have been 70 percent against it (in a public poll).

Still, community unease didn’t stop Purchase and the ardent group of supporters he’d attracted along the way, including Reid, then-County Councilman Dennis Flannigan and Lyle Quasim, who worked as the state director of mental health and later with Safe Streets, from persisting.

“I had seen one of the methadone treatment clients with AIDS, who had transferred from a San Francisco program and literally withered away and died in our program,” Reid said. “I was also plugged in to some of the research taking place on the East Coast, particularly New York, where the number of AIDS cases were just exploding relating to IV drug use.

“I thought, ‘My god, we’re in a position where we could do something about that.”

So Reid agreed to help.

“It was an opportunity, and fortunately I was sort of in the right place, and brave enough — and careless enough with my career — to forge ahead,” he said. “It just seemed like the right thing to do.”

Challenges to the program have been a near constant throughout its three decades. Nearly seven years after it began, then City Councilman Steve Kirby spearheaded an effort to try to drive it out of Tacoma.

As The News Tribune’s Barbara Clements and Elaine Porterfield reported in 1995, Kirby’s crusade struck themes that were surely familiar to Purchase — arguing that syringe exchange promoted crime and condoned illegal drug use.

“I don’t believe we should be handing out needles to addicts,” Kirby told The News Tribune 23 years ago. “I think we ought to be arresting them and getting them off the street.”

Reached this week, Kirby couldn’t help but chuckle when presented with his past bluster. In many ways, Kirby’s evolution is indicative of the way society’s perception of needle exchange and preventative public health have changed over the years.

“Those were times when I was quite the big crime fighter and neighborhood activist. I would do whatever it took to defend my neighborhood and neighborhoods throughout Tacoma,” Kirby said, acknowledging that there was likely some political posturing behind his remarks from the time.

“I would not be surprised I that’s exactly what I said. If you guys wrote it, it was true” Kirby continued. “For the record, if I ever believed that, I don’t believe it now. I think it’s a dumb idea to arrest drug addicts and throw them in jail.

“I haven’t heard a complaint about the needle exchange in I don’t even know how long — decades.”

Quasim also can’t help but be surprised by what the effort accomplished, and the societal shift it helped inspire.

“The environment, on a scale to 1 to 10, the sympathy in our community was maybe running around a 2 or 3 at best. People really seemed to have their minds made up about (AIDS) being a disease that was the fault of the person who had it, or that they’d engaged in nefarious behavior and it was punishment,” Quasim recently recalled.

Purchase helped change that.

“Whether it was Dave’s karma, whether it was just rational thought or whether it was that the moon was in the seventh house and Jupiter aligned with Mars, I don’t know. But we had the police chief and the health department on board with this thing,” Quasim said. “It was a health issue. We stayed with it because it became a values proposition for us to continue the program.”

Through it all, Purchase remained the guiding force of the Point Defiance AIDS project and the Tacoma Needle exchange. Flannigan, who went on to serve on the Point Defiance AIDS Project’s board of directors, remembers Purchase as “the brightest ship in the country.”

Alisa Solberg worked for Purchase for 20 years and served as interim and acting executive director of the Point Defiance AIDS Project from shortly before his death until 2016.

“Dave would always say the point (a clean syringe) is the point,” Solberg recalled. “He could appeal to legislators and lawmakers and policy people and get them all marching in the same direction.

“He was also able to reach people who were unreachable, untrusting, invisible — people who you and I would not be able to reach,” she continued.

“And that’s just unheard of, for a person to move in all of those circles.”

A new challenge

Today, while the national AIDS crisis has subsided, current Point Defiance Aids Project executive director Paul LaKosky says needle exchange in Tacoma and Pierce County remains as important as ever.

There’s one big reason for that: the ongoing opioid epidemic, which has afflicted a new generation of IV drug users, with deadly consequences.

In this, the Tacoma Needle Exchange has been forced to evolve. While the Tacoma Needle Exchange’s work now includes both the prevention of HIV and AIDS and hepatitis, saving lives and alleviating other public health concerns associated with IV drug use remains the constant.

The quest still relies on swapping out dirty needles for clean ones at various locations around Tacoma — including the parking lot of the health department and the use of a van for rural deliveries of supplies. It also means connecting those suffering from addiction with essential services, and the distributing Naloxone, an emergency medication that can reverse the effects of an opiate overdose.

According to LaKosky, the Tacoma Needle Exchange distributed more than a million clean syringes throughout the city in the first six months of this year. Nationally, through NASEN, more than 100 million needles were handed out.

It’s a far cry from the 13,000 Purchase distributed from his television table downtown during the first five months of the program he created almost single-handedly.

LaKosky sees no slowdown in sight.

“The growth has been exponential, and even at that, we’re still not meeting the demand,” said LaKosky. “It’s kind of ironic, I think, that the 30th anniversary of the first legal syringe exchange in the United States also seems to converge with the emergence of a huge opioid epidemic.

“After 30 years, the services this organization has provided are even more necessary than ever.”

READ MORE THE TACOMA NEWS TRIBUNE